Emotional Beats in Storytelling (Part 3: Action Beats)

This is the third part of a series on emotional beats; the parts of a story that are used to make individual scenes and events interesting. If you haven't already, I'd suggest going back to check out the overall introduction.

Action beats are the meat and potatoes of storytelling; they’re basic units that you can use when you’re putting a story together, and they’re especially important for game designers, because we wind up using a lot of them when we can’t use other things.

There are really two purposes of action beats: broad “excitement” or the creation of a particular emotion, and the former is by far the more common use.

The Action Beat

The action beat is one that focuses on having the audience witness certain events, and it’s perhaps the most broad of the individual categories of beat.

One of the interesting things about the action beat is that it is a reflection of the stored tension of the story. Action with nothing behind it feels cheap (this is why people who don’t have an appreciation for a good action film don’t like them), but it also is a great way to highlight important events in a story.

The film John Wick, and its sequels, are often considered the second coming of action films, and they’re tremendous for delivering non-stop action in ways that make sense. They’re a lot slower-paced than you might expect from an action film (though many action classics, like Die Hard, Terminator, and Commando are similarly slow-paced through much of the film), but the point of this is to blend the action beats with suspense beats and intimate beats.

By the time you’re about fifteen minutes into John Wick, you’ve got such a feel for the character that the action beats explain something about him; he's already been introduced to us and the story is advanced by them.

Traditional Action Beats

It's worth noting that you can split action beats into two categories. They function similarly in terms of what you might expect to see; a fight, a verbal altercation (or more subtle form of people one-upping each other, as seen in a business-card comparing scene in American Psycho), or some other high-stakes event.

However, they can be divided into two general types.

Spectacles are "cheap"; they can fit anywhere in the story, but excel when there's already low tension, and help to draw in an audience's interest. In John Wick, we get our first spectacle thirteen minutes into the film, when he takes his car out for a reckless drive at a closed track. Spectacle is impressive, but wears thin quickly. We learn that John's a good driver who has a fancy car and knows how to use it in this scene, and that he's also taking risks because he's stopped caring about things after his wife's death. The filmmakers combine it with an intimate beat, where we get to see inside Wick's head, but are also aware of the fact that for an action film they're just about hitting the limit of how long they can film without giving us an action scene.

The other type of beat is a resolution beat, where a previous piece of information becomes the spark for some event. In John Wick, the next scene after John's high-speed drive is pay-off for an earlier suspense beat. John had gotten into an argument with some Russian mobsters at a gas station who want to buy his car even though he refuses to sell it. In this scene, they break into his house, beat him up, kill his dog, and take his car; this serves as a resolution to the former suspense, and we see the tension flow upward here.

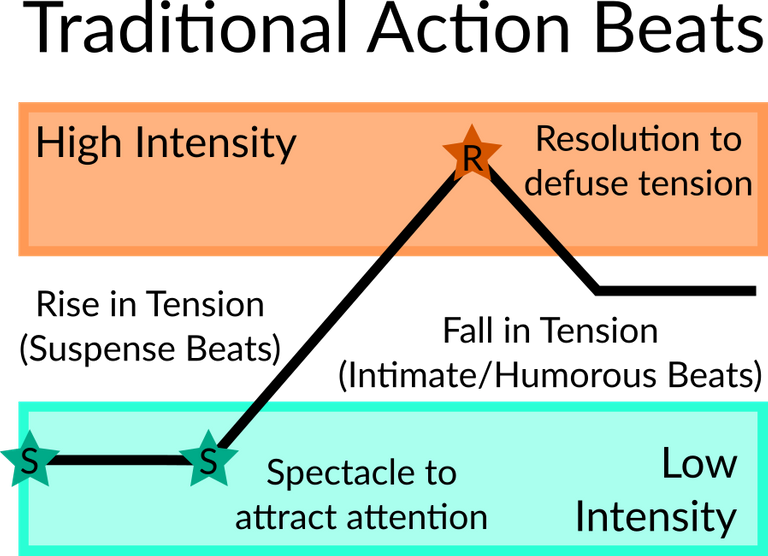

Diagram of how action beats relate to tension in a story.

One of the things that's worth noting about John Wick is that both types of action beat come at a time of relatively high intensity, though it's intensity that the audience hasn't necessarily caught on to yet. This is because they tie into different threads of the story; at this point in the story Wick's loss and grief over his wife is at a point of low tension; he's shattered by it, but he hasn't figured out how to move on yet (this thread continues across the three films that have already been released), but the thread that dominates the first film is that of Wick's confrontation with the gangsters who killed his dog, which has already been set into motion by the gas station encounter.

Weaving the two together helps with pacing; it would be too obvious and feel cheap if the gas station encounter led directly into the home invasion, even though they belong to the same story-line.

Spectacle

Spectacle is the action beat that allows us to set the tone. Unlike other action beats it can be used to great effect even when the tension is low, but it also wears thin quickly.

Personally, I label the evocation of the muses as a spectacle beat in the Iliad, because the point of the it is to point out how large and important the events going on are. We don’t always appreciate this, because the Greeks had less access to CGI than we do, but the events depicted in ancient epics are often presented in this way (Beowulf is another good example).

The thing about spectacle is that it doesn’t use up and resolve tension in any way. It’s the storytelling equivalent of iceberg lettuce; it takes up a lot of space, but it isn’t going to provide any serious storytelling.

Spectacle is often used at the very start of a story because it draws an audience in and it helps the storyteller start at a high point. It doesn’t necessarily have to be particularly impressive; the classic hook where someone says “Hey, I’ll tell you a story about X, who did Y!” goes all the way back to Homer, and it still works to this day if the things you insert in X and Y are interesting.

Within a story, spectacle can be used to set the tone and stakes. Of all the action beats, it tends to be the only one that pushes tension upward, but it doesn’t do a very good job of it. That’s what suspense beats are for. Look at A New Hope, where the opening combat serves as a reminder of the stakes for an example of this done right.

Be forewarned that spectacle still needs to be active. Panning landscape shots have their place, but they’re not an emotional beat, and if they are they lean more toward suspense than action. A lot of spy thrillers will use their environments to build tension by showing us a spectacle, but that’s a different sort of thing than the spectacle beat.

Resolution

The most traditional form of action beat is the resolution. Resolution beats take conflicts that have been established and have them boil over.

Think of this like the transmutation of tension into enjoyable story moments. If you just show us a secret agent in the middle of a city-spanning chase-fight hybrid at the start of a film, you’re not giving us an enjoyable resolution. You could use it as an intimate beat (e.g. letting us know what the agent’s capabilities are), or as a suspense beat (e.g. letting us know that thte agent is in trouble), but these do not require a long sequence.

Resolution beats are not for exposition, unless that exposition is a climactic revelation (“Luke, I am your father!”), so you want to keep them unblended as much as possible.

Resolution is when the protagonist does what they have to do to get what they want; they confront the bully, they overcome a personal limitation, they make it to space.

You can have small resolutions; I’m not referring to the sort of resolution you’d see in an English class plot diagram.

To use the dubious example of The Phantom Menace (it has a resolution beat that’s competently executed early in the film), there’s a great early scene where the Jedi knights are nearly assassinated by the Trade Federation. Instead, they turn out to be immune to the gas used to kill them and fight their way off the station.

This is a resolution beat. A problem was already brought up through suspense beats, and the resolution beats answer those problems.

Resolutions don’t always have to go in the protagonist’s favor, though.

In the example we used from John Wick earlier, the resolution of the suspense was that Wick loses hard and gets a motive that will carry him through the rest of the film: revenge.

Resolution reduces tension, or clarifies and refines the ongoing plot threads. If it’s just senseless violence or conflict, it wears thin quickly and gains all the flaws of meaningless spectacle. It needs to transform the protagonists or their understanding of the conflict that the beat is tied into.

Sex and Action

I have a general rule for sex scenes: I skip them. But I’m a Puritan and storytellers don’t always get that luxury. It’s a part of life, and while it’s one that I’d usually depict with the surrounding events rather than the horizontal tango, it is nonetheless something that will happen in storytelling.

Fortunately for the prudish, most sex scenes (at least in recent days) are spectacle rather than story advancing.

I’m going to cover this more later, but for now know that a lot of sex scenes, especially the more graphic or fast-paced ones, tend to be action beats. They exist for prurient interest, in which case they can really be quite a spectacle.

Sex can serve as a resolution, whether it’s shown closely or not. Romantic tension is one of the forms of suspense, and it can also reflect the relationships shown in more intimate scenes being strengthened, weakened, or transformed.

Keep in mind that sex is a nuclear subject, even as the depiction and discussion of it has become less stigmatized. If you’re writing for a game, keep in mind that interactive sex scenes are basically X-rated even if they’re not particularly graphic or explicit (e.g. the sort of vague movements and outlines you might even be able to get away with on TV become troubling when you actually guide them). It’s also one of those places where you can easily upset players who don’t want what you’re selling.

BioWare used to handle this pretty non-controversially (as far as anything related to video games and mature content can skirt controversy) in the early Mass Effect and Dragon Age games; there were romance options that were pretty much exclusively intimate and suspense beats, with player direction, and rather-hands off resolution that played out off-screen or in very blurry day-time soap opera scenes.

Dialogue in Action Beats

One of the interesting things is that in some stories you can have action beats delivered in dialogue. This is distinct from exposition (as could be seen in some intimate or suspense beats), because it has a role in furthering the plot.

Dialogue often serves to blend the role of an action beat with one of the other beats. If we see our action hero fighting through a whole pack of bad guys, and then at the very end someone asks him “Why?” and he says something like “You killed my dog!”, then we wind up with an intimate beat being blended in with an action beat.

A Streetcar Named Desire has some tremendous blending of action with dialogue; it’s a story full of arguments and strife, and though much of the dialogue builds suspense Williams also uses it to carry the action as well: the story centers on emotional and sexual abuse, and as often as not the audience’s only confirmation of events comes in the conflict between people.

This is a lot easier when combined with visuals; we can read body-language and see exactly what’s going on, though some writers do a good job of communicating this through words on the page. The important thing to remember is that dialogue wants to be something other than an action beat, and you need to keep it flowing fast. If you have a character like Sherlock Holmes score a win in dialogue by outsmarting someone or a character like Amos Burton in The Expanse scare the socks off of someone without raising his voice, that’s action dialogue. It’s rare, but when it gets pulled off it’s a great moment.

Action in Games

Action beats are the game’s bread and butter. Both in video games, where they are the easiest sort of emotional beat to deliver, and in roleplaying games, where players bring a lot of the other storytelling beats with their characters and the game designer has less control over how they are conveyed, the action beat is simple and versatile, gluing together all sorts of pieces.

Action and Audience

The biggest challenge with getting action right in a game is to deliver on the type of action players want.

There are really two questions to answer here:

What does your audience want to see?

What goes in line with what your story needs?

I’ve seen people go all over the place with these two questions, and a lot of this is what leads into bad action films or worse action-oriented games.

The worst example I’ve ever seen of this came in the form of EA’s rebooted Syndicate, a first person shooter take on the classic squad tactics game. I actually really enjoyed it (and I don’t truck much with nostalgia when it comes to genre of games), but there was one moment about half-way through the story that absolutely destroyed it for me.

You take on the role of Miles Kilo, corporate agent. And, quite honestly, he’s got one of the more awesome pairs of shoes to step into. Big guns, techno music (of varying quality), sleek futuristic aesthetics and action.

About half-way through the plot, someone convinces Kilo that he’s working for the wrong side and he defects, sort of the classic plot you would see in an action or spy thriller and evocative of the classic Deus Ex.

Except that I wasn’t sold, and I don’t know if the rest of the audience was either. There was this “giant corporations are evil!” plot, but the resolution of it wasn’t to tear down the system but to work with a known double-agent. At the end of the story the climax was “You’re free now!”, but when Kilo made the decision to work toward that it didn’t feel like he was moving that direction: one evil corporation is not better than another.

A lot of action is centered around the high-school teachings about the Hero’s Journey and the plot diagram (first you build tension, then you release it), and that’s not bad, but you need to realize that action is more than just tension and release.

It’s about moving in a satisfying direction.

Make sure that every point of action ties back to suspense beats (which justify it) and intimate beats (which foreshadow the character’s actions). If you’re giving the player freedom, make sure that freedom counts. Emergent systems are great for this. If I’m playing Fallout and someone betrays me, I have the opportunity to talk to them (and then maybe get into a fight with them), but I could just as easily wait on the other side of the map with a sniper rifle and take a cheap shot at them. Dialogue trees and scripted events work as well, but bear in mind that they’re expensive.

In roleplaying games, the game designer needs to make sure that players have the tools at their disposal to tell the right kind of story.

I recently reviewed a roleplaying game called Justice Velocity, and one of the things that it does really well is featuring just the rules that players need to give them the action experience. Because it generally has rules for everything you’d see in an action movie, but gives a focus on combat and vehicles (two things you are likely to see a lot of in action movies), it is able to deliver a satisfying experience while also being just over 70 pages of rules and content where most roleplaying games can run around 200 to 300 pages.

My own game, Hammercalled, is built around the idea that everything is modular and things like skills and gear can be defined largely by their role in narrative. Characters can get bonuses associated with statements like “I am able to hack things: and a tool that says something like “Get a +10 when hacking a security device” without my needing to put that into the system explicitly. It won’t quite hit the same level of granularity you could hit in a more setting-specific game, but you could add those elements as a layer over the top if you need them.

Action through Gameplay

Action beats are predominantly focused on excitement.

For someone telling stories through a game, you want to be able to utilize this quite well.

To use an example from Syndicate again, there’s a scene in which Kilo finds himself standing atop a train and fighting bad guys while hacking drones. Because the controls are fluid and there’s lots of high action, it’s one of the best spectacles I’ve ever seen in gaming.

A lot of action beats can come about through emergent play. Dark Souls has its boss-fights and encounters with enemies, which are great for offering both the intensity of action and a healthy dose of fear in occasions where the player is unprepared for the fight.

It’s worth noting that these action beats generally do little for stories; where Syndicate ostensibly ties its fight into its narrative (lousy as it generally is), Dark Souls has boss fights that are tremendously meaningful (Sif) and ones that are basically meaningless to most players (capra demon).

Action beats by themselves can make a game engaging. We’ve known this since Pac-Man, or perhaps even before that. Yeah, there’s usually a flimsy framing narrative over the top, but nobody’s saying that games like Distance or Audiosurf are less satisfying because they deliver action outside the boundaries of a conventional story.

One of the nice things that games can do that non-interactive media can’t is to make the stakes personal. We need strong stories in even action-oriented films because otherwise we don’t have a connection to the ation. In a video game or roleplaying game, the action beats determine whether the player wins or loses. That goes a long way.

Wrapping Up

Action beats deliver intensity to reflect the tension that has been built up over the course of the story. They entertain the audience but they also play a key role in delivering the expectations; without them it’s difficult to bring together a complete narrative. By themselves, however, they don’t deliver on the stakes that we need to emotionally invest in the story.

We’ve already talked about humorous beats. We’ll look at intimate beats next, then move to suspense beats before a final recap.

To listen to the audio version of this article click on the play image.

Brought to you by @tts. If you find it useful please consider upvoting this reply.

This post was shared in the Curation Collective Discord community for curators, and upvoted and resteemed by the @c-squared community account after manual review.

@c-squared runs a community witness. Please consider using one of your witness votes on us here

Everything's better with a !BEER :)

To view or trade

BEERgo to steem-engine.com.Hey @loreshapergames, here is your

Do you already know our BEER CrowdfundingBEERtoken. Enjoy it!Congratulations @loreshapergames! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPHello @loreshapergames, thank you for sharing this creative work! We just stopped by to say that you've been upvoted by the @creativecrypto magazine. The Creative Crypto is all about art on the blockchain and learning from creatives like you. Looking forward to crossing paths again soon. Steem on!