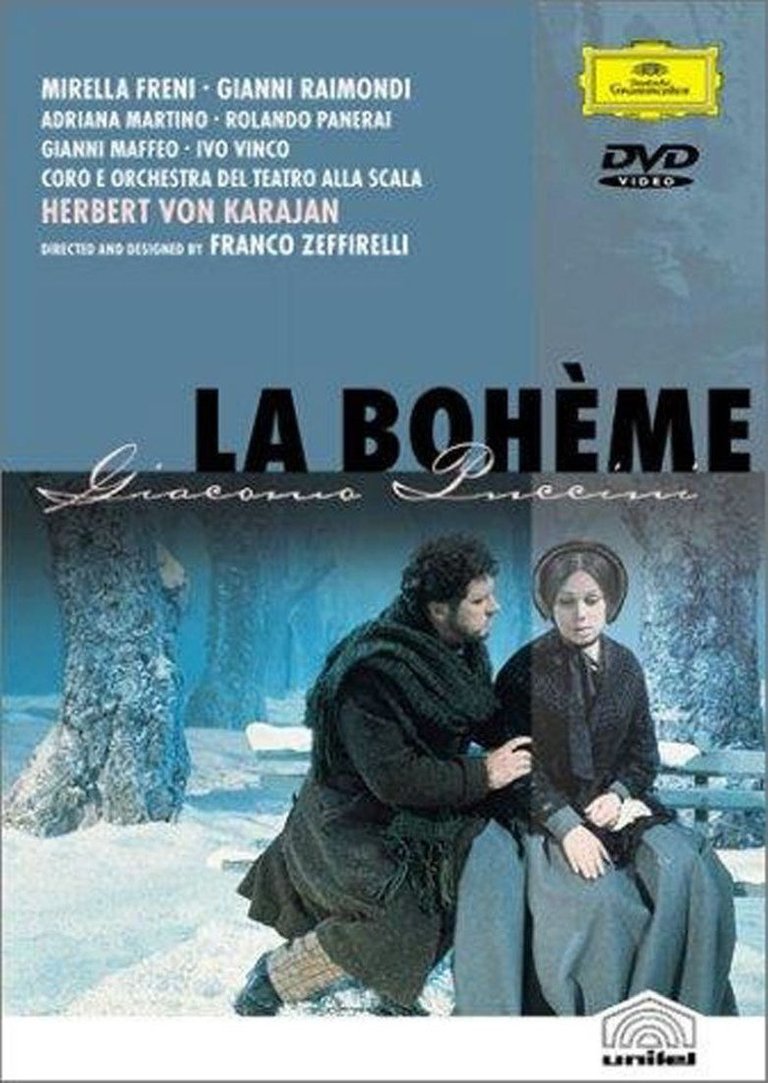

REVIEW: La Bohème (1965)

La Bohème, dating from 1965, is widely considered among the best opera films ever made. The great Franco Zeffirelli provided the production design and the equally renowned Herbert Von Karajan conducted the orchestra. Ultimately, however, the triumph owes the most to the composer, Giocomo Puccini (1858-1924).

Historical Background

Puccini's third opera, Manon Lescaut (1893), was the first to earn him widespread recognition, yet not so much as the quality of the work deserved. It's reputation suffered from inevitable comparisons with Massenet's Manon, which was that composer's undeniable masterpiece. Puccini labored for the next three years on the opera that would ultimately become the foundation for his international fame, La Bohème. The impresario Giulio Ricordi had introduced Puccini to two young librettists by the names of Guiseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica. Puccini was not an easy composer to work with, but the pair of writers ultimately generated one of the finest opera librettos ever devised, adapted from Murger's Vie de Bohème. The subject matter of the libretto was ideally suited to Puccini's creative muse. Puccini always had a natural empathy for frail women so it comes as no surprise that he wrote some of his most exalted music for the character Mimi. Furthermore, Puccini had his own experiences with the Bohemian lifestyle during his days in Milan. The only drawback in proceeding with this particular score was that Leoncavallo was working simultaneously on an opera with a score based on the same source material. Puccini was accused of poaching. La Bohème had its premiere at Turin on February 1st, 1896, three years to the day after the premiere of Manon Lescaut. Surprisingly, the new opera was not as immediately successful as its predecessor, but its reputation grew with every performance until, today, it is rivaled only by Bizet's Carmen as a favorite among the public.

Although Puccini is sometimes afforded only grudging respect by musicians when placed beside Mozart, Verdi, Donizetti, or Rossini, La Bohème has stood the test of time. In addition to the charm and emotional power of both the libretto and the score, Puccini imbued this opera with a rich variety of orchestral techniques, all managed with utter mastery. Who but Puccini would incorporate a glockenspiel, chimes, or a kettledrum? Who but Puccini would use such daring harmonies and modulations? Puccini also had a great gift for theatricality, necessitated in part by the changing requirements of operatic composition. Whereas his great predecessors had the convenience of recitative to segue between arias and provide expository functions, Puccini's era demanded the entire story be told in the form of a continuous stream of music. That development in operatic style put great pressure of both librettists and composers, but also resulted in works of greater theatrical continuity. There are fewer lapses in dramatic intensity. Puccini never keeps us waiting for our next musical or dramatic fix.

The Story

La Bohème is an opera in four acts. Act I finds Rodolfo (Gianni Raimondi), a poet, and his friend Marcello (Rolando Panerai), a painter, struggling in their cold Parisian garret. It is Christmas Eve, but they have money for neither fuel nor food. Their desperation is so great that Marcello offers to burn one of his canvases, but Rodolfo sacrifices first one act and, then, another, from his latest play. Colline (Ivo Vinco), a philosopher, joins them, in an equal state of desperation. When the fourth member of their group, Schaunard (Gianni Maffeo), returns, all are delighted to learn that he comes with both money and provisions, having been well paid for a music lesson provided for a gentleman (and his parrot). The foursome decides to celebrate by eating out in the Latin district. First, they have to put off Benoit (Carlo Badioli), the landlord, who comes by to demand the last quarter's rent. Rodolfo stays behind to finish an article he's writing for The Beaver, but promises to catch up with the others.

Rodolfo, now alone, hears a knock at the door. It is Mimi (Mirella Freni), a young woman from a neighboring apartment, whose candle has gone out and has come to ask Rodolfo to relight it. After the wind blows out both his candle and her re-ignited one, Mimi drops the key to her apartment. As the two search for the missing key in the darkness, their hands meet, not entirely inadvertently. Soon, the pair is exchanging life histories and professions of love. They go off to join Rodolfo's friends to celebrate.

In the Latin Quarter, in Act II, Rodolfo buys a pink bonnet for Mimi as a token of his love. The love-struck pair then join Rodolfo's Bohemian friends at the Café Momus, where they order liberally. The evening takes a dramatic turn with the arrival of Musetta (Adriana Martino), Marcello's former lover and an inveterate flirt, dressed in a gorgeous, bright red evening gown. Musetta's escort is a wealthy older man, Alcindoro (Virgilio Carbonari), a counselor of state. Marcello, well aware of his weakness for Musetta, tries to ignore her, but his seeming indifference simply infuriates her. Musetta amuses all of the patrons of the café with a brash, flirtatious song, declaring, "When I walk down the street, people turn and stare at me. They survey my beauty from head to foot. And I enjoy the hidden longing that gleams in their eyes as they imagine the hidden charms beneath my visible attractions." All Marcello can do is beg his companions, "Tie me to the chair." "She eats hearts," he tells Mimi, "That's why I haven't got one." Musetta's trap setting, however, is as pleasant to the prey as to the hunter. Musetta cleverly contrives to send her escort on an errand and the lovers and friends head off together, leaving the bill for Alcindoro, when he returns.

Act III is a cold dawn in February, outside a tavern, close to one of the gates of Paris. Mimi enters in search of Marcello, who is working at the tavern, along with Rodolfo. Mimi explains to Marcello that she and Rodolfo have been quarreling, apparently driven by his insane jealousy. When Rodolfo awakens in the tavern, Mimi hides behind a tree before Rodolfo emerges. Pressed by Marcello, Rodolfo admits that his real motivation for wanting to send Mimi away is that he fears for her health and is ashamed that he can provide no more for her than a cold, dark room. Mimi reveals herself and the lovers try to say goodbye to one another, but are unable to do so, finally agreeing to stay together until spring, as Musetta and Marcello quarrel in the background.

Act IV takes place back at the garret. Several months have passed. Rodolfo and Marcello are doing their best to concentrate on their work, but are distracted by remembrances of their respective lost loves. Colline and Schaunard enter and the four Bohemian friends engage in some clowning around until Musetta suddenly enters and interrupts them. She has found Mimi alone on the street in dire health and too weak to climb the stairs. Rodolfo helps her up the last few stairs and into the room, where she is quickly settled onto a bed. Mimi is dying from tuberculosis. Musetta removes her earrings and Colline his coat and the pair head off to a pawn shop to raise money to buy medicine for Mimi and a muff to warm her cold hands. Marcello and Schaunard go out in order to leave the lovers alone. After a few minutes, the others return and Musetta prays for Mimi, but it is to no avail. Mimi quietly dies and the distraught Rodolfo can only cry out her name.

Themes

The central theme, I think, is that there is no more difficult manifestation of love than being there for a loved one when their time to die has arrived. A less obvious thematic question is why we, as a society, can provide nothing better in the way of an existence for artists, philosophers, musicians, and poets.

The libretto for La Bohème certainly ranks among the greatest in the operatic literature. Act I begins with a heartrending display of the ravages of poverty, but ends with the promise of love. Act II is a masterful piece of comic relief embedded in an opera that is largely tragic drama. Then, immediately on the heels of the exuberant gaiety with which Act II climaxes, the emotional tone of the story plummets like a snowball into the depths of wintry calm. Like Act I, Act III ends with balm afforded by promises of undying love. Then Act IV brings the tragedy to its inevitable but emotionally wrenching conclusion.

Puccini's work is so inherently dramatic that it defies the conventional wisdom that opera is not very cinematic. La Bohème may be the rare instance of an opera that is potentially a good deal more effective on celluloid than on stage. Certainly, the production engineered by Franco Zeffirelli makes it so. The magnificent sets, featuring painted backdrops, are not so much realistic as poetic, adding a visual counterpoint to the powerful music. The sets feature mostly muted earth tones that reflect the austere conditions of the Bohemian lifestyle. The soft, drab color scheme also highlights the occasional splashed of bright colors, such as Musetta's flamboyantly red dress in Act II. The other great benefit from seeing the opera on screen rather than stage is that the frequent close-ups of the central characters permit viewers an intimacy with the proceedings that can never be provided at Covent Gardens, La Scala, or the Metropolitan. And La Bohème is, after all, the most intimate of operas.

The advantage of facial close-ups might have been less important were it not for the tremendous performances provided by the entire cast, but most especially Mirella Freni and Adriana Martino. These are two of the finest performances that I've seen on film, not merely in cinematic renditions of operas, but in films of any kind. Freni, who has the opera's crucial role, beautifully captures both the passion and the demure timidity of Mimi. The marvel, however, is the subtly of her facial expressions. Freni knows how to deliver tantalizing half smiles and fleeting glances as well as any actress you'll find. She makes you share Rodolfo's love for her and, hence, all the agony of the final loss.

Act II, however, belongs almost entirely to Adriana Martino. Musically, it is my favorite individual act from any opera. I've listened to it at least fifty times in my life, perhaps a hundred times. The scene in the Café Momus is a masterpiece of ensemble singing, with Musetta acting as the spider and all of the others her web. Martino's comedic timing during the scene is spectacular. Every insolent gesture, every facial expression, even the movements of her eyelids highlight what the scene is expressing. Musetta is the ultimate flirtatious vamp, a femme fatale without parallel. Martino plays the part with such perfection that you'll be left slack-jawed with admiration. You know those rare instances in cinema when you encounter a villain who has perfected villainy to such an exquisite art form that you actually have to admire the character? Martino, playing Musetta, takes the idea of a dazzling tease to that kind of zenith.

I don't mean to slight Gianni Raimondi's work as Rodolfo or Rolando Panerai's performance as Marcello. Both manage to look younger than their actual years, portraying convincingly the destitution of the Bohemian existence. They are the foils for the women, however, providing the vantage point from which the audience can observe the two strikingly different female leads. Ivo Vinco, as Colline, proves a fine actor as well.

All of the performers are in fine voice and who could fault the conducting of Herbert Von Karajan or the performances by the Chorus and Orchestra of the Teatro alla Scala? My one complaint about this film is that the post-dubbed soundtrack is not always perfectly synchronized with either the lip movements of the singers or to the dramatic action. Act I, for example, ends with a final couple of notes sung by Mimi and Rodolfo from the corridor as they are leaving and closing the garret door, but the notes are rendered on the soundtrack as though the pair were half-a-block down the street. It's a small quibble, however, in light of the overall magnificence of Zeffirelli's conception and the performances by all involved.

Many of the greatest opera stars do not really have the physical attributes for the roles they inhabit, and cinema makes such deficiencies more apparent. Zeffirelli went out of his way, for this production, to find stars who were musically gifted but who also had the physical appearance and acting skills to render their roles with visual authenticity. Considering only the music, I would still choose my audio version, featuring an all-star cast of Victoria de los Angeles, Jussi Bjoerling, Lucine Amara, Robert Merrill, Giorgio Tozzi, John Reardon, and Fernando Corena, but I very much doubt that group could have matched, at any stage in their careers, the visual effectiveness of Zeffirelli's cast.

This filmed opera is one of the most cinematic that you'll find. This rendition not only makes full use of the potential of cinema, but it may actually be more satisfying, dramatically, than any performance you'll ever see on stage. That's because the potential for close-ups is especially important for this highly intimate opera. This is, quite simply, one of the greatest cinematic adaptations of opera done so far. La Bohème is a great entry point for those wanting to explore opera for the first time, so I highly recommend this film both for established opera lovers and would-be novices. You just can't do any better.

Congratulations @devoran! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Your next target is to reach 2250 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP