REVIEW: Boris Godunov (1954)

My personal preference, in choosing opera films, is, whenever possible, to go with performances from the country of origin of the opera. The reason is quite simple. Nobody understands the cultural context of an opera as well as the people of that culture. This is even more true of Russian opera than the more frequently rendered staples of the repertoire, by the Italian masters or the Austrian Mozart, which have acquired greater universality of performance. I would rather see Boris Godunov, for example, performed and filmed by the Bolshoi, using authentic locations for many of the scenes, than a staging by the Metropolitan Opera in New York, no matter how lavish the sets. That's just my preference, based on cultural authenticity. It is for that reason that I recommend this 1954 version of Boris Godunov, directed by Vera Stroyeva, over some attractive competition. Boris Godunov was the product of the great composer, Modest Mussorgsky

Historical Background:

Modest Petrovitch Mussorgsky was born in Karevo, a small village in Russia in March of 1839 to a family of wealthy landowners. He entered the School for Cadets of the Guard in St. Petersburg in 1849 to prepare for a career in the army. He exhibited a talent for music, as a quiet and studious child, taking up the piano. The regiment of cadets that he joined in 1856 were a hard drinking lot and Mussorgsky's musical talents won him many friends. He began the study of musical composition with Balakireff in 1857 and resigned his commission the following year in order to devote himself to music. After the liberation of the serfs in 1861, Mussorgsky's family was thrown into poverty. Nevertheless, Mussorgsky continued to develop as an artist. His ideas were influenced by emerging ideas of realism in art as well as the nationalism that had been introduced into Russian music by Glinka. Mussorgsky wrote many "peasant songs" between 1864 and 1867 and began work on his first opera, though it never reached culmination.

Mussorgsky began his unprecedented masterpiece, Boris Godunov, in 1868 and completed the initial form of the opera in 1869. After it was rejected by the Imperial Theatre, Mussorgsky remodeled the opera during 1871-2. The entire third act (the so-called "Polish Act") was added in the second version to provide a love interest. The revised version was performed once, on January 24th, 1874 and published later that year. The genius of the work went unrecognized even by Balakireff and Rimsky-Korsakoff. It was simply too unlike what was being crafted by the academics. No one but Mussorgsky could have created such a masterpiece. Mussorgsky was possessed by a rough-edged, natural genius and unconstrained by the traditions or dogma of the professional musicians. Mussorgsky's financial, mental, and physical condition deteriorated relentlessly, as he dealt with poverty, menial work, alcoholism, and the torments of guilt. He died a tortured soul in 1881 at just forty-two years of age.

After the initial performance of Boris Godunov, a few critics hailed the work as the vanguard of a new era of enlightened nationalism, but the vast majority of critics and musicians found the work vulgar and amateurish. The dissonant harmonies were unlike anything that had been heard before. Rimsky-Korsakov, who was a highly influential person in the musical establishment of Russia and a master craftsmen, simultaneously acknowledged the raw genius of Mussorgsky's work while being repelled by what he called Mussorgsky's "obstinate amateurishness." Rimsky-Korsakov later acknowledged that "He hated Boris and he worshipped it." After its initial performance, Boris Godunov sunk into oblivion until well after Mussorgsky's death. It was Rimsky-Korsakov who salvaged it.

In 1884-5, Rimsky-Korsakov completed, revised, and reorchestrated Mussorgsky's other great operatic masterpiece, Khovanshchina, which Mussorgsky had left unfinished at his death, and, gradually, this new version of Khovanshcina was established as part of the operatic repertoire in Russia. Rimsky-Korsakov was thus emboldened to take up the task of a revision and reorchestration of Boris Godunov in the 1890's. In doing so, Rimsky-Korsakov made drastic cuts, inserted new music, and "corrected" some of Mussorgsky's more innovative harmonies. Twelve years later, motivated perhaps by pangs of artistic conscience, Rimsky-Korsakov produced another version that restored the cuts. The second version by Rimsky-Korsakov is the one most often performed today, typically with a few cuts and reversions in keeping with Mussorgsky's own final version. Another reorchestration was undertaken by Dimitri Shostakovich in the 1940's, which is generally less opulent than the Rimsky-Korsakov versions but more so than Mussorgsky's own versions. The 1954 recording by the Bolshoi is based on Mussorgsky's second version, with some cuts. The final irony is that most of the "blunders" and "inadequacies" observed in Mussorgsky's harmonies later became standard elements of twentieth century music!

The Story

The story of the opera develops in a prologue and four acts, most with multiple scenes. On the death of Ivan the Terrible in 1584, the great Tsar left behind two sons – the mentally incompetent Feodor and the small child Dmitri. Ivan also had a brother-in-law, Boris Godunov (Aleksandre Pirogov), who was an ambitious schemer. Godunov had Dmitri murdered. When Feodor later died, Godunov cloistered himself in the Novodevichi Monastery near Moscow, feigning humility, while secretly ordering his troops to coerce the people into gathering in the courtyard of the monastery to implore Boris to assume the mantle of leadership of the country. As the Prologue opens (Scene 1), the palace guard prods the people to kneel and supplicate Boris to accept the crown of the Tsar. Boris, however, stealthily remains resolute in his false humility. A chorus of pilgrims, first heard in the distance, arrives to join the entreaty. Later (Scene 2), in the square outside the Kremlin in Moscow, as the people kneel, a procession of Boyars, regally clad, moves toward the Cathedral of the Assumption, as the bells of the cathedrals peel gloriously. Rising from the midst of the procession, the newly crowned Boris implores the almighty to help him "rule over my people in glory."

Act I opens in a humble cell in the Monastery of the Miracle (Scene 1). There are just two people in sight, though a few monks can be heard offstage praying for the "Evil One." An old monk, Pimen (Maksim Mikhajlov), works at a writing table, chronicling recent events in a book of Russian history. A younger novice, Grigori (Georgi Nelepp), lies asleep on a cot. Suddenly, Grigori awakens with a start and relates a nightmare of being pursued by the devil. Grigori learns from his cellmate that he is the same age as the murdered Prince Dmitri. Pimen, who had witnessed the discovery of the murder of the Tsarevich recounts the scene in vivid detail to Dmitri. Later (Scene 2), Grigori has fled Moscow obsessed by a wild ambition to seize the throne by claiming to be Prince Dmitri. He has reached an inn on the Lithuanian border, where the Innkeepers wife (A. Turchina) sings a lovely folk song. Two wandering friars, Varlaam (Aleksej Krivchenya) and Misala (Venyamin Shevtsov), arrive at the inn at about the same time as Grigori. Varlaam gets a little tipsy and sings a robust drinking song recounting a former triumph of Ivan the Terrible. The border patrol suddenly arrives, under orders to find and seize a dangerous fugitive from Moscow. They are carrying a description of the fugitive (who is obviously Grigori), but none in the company can read, save Grigori. Grigori offers to read the document, but alters it as he reads to describe Varlaam rather than himself. Varlaam is seized but, now desperate, demands to see the warrant himself. Though not a proficient reader by any means, Varlaam is able to sound out words letter by letter. As he struggles through the description, literally reading for his life, it becomes apparent to all that it is Grigori, not Varlaam that the arrest warrant describes. Grigori, the Pretender to the throne, pulls a knife from under his cloak, leaps out a window and escapes.

Act II has only a single scene. In the Tsar's magnificent chamber in the Kremlin, Boris' two children, Feodor (I. Khmelnitshy) and Kseniya ("Xenia") (N. Klyagina), are with their old Nurse. Feodor is studying a book. Xenia is examining a portrait of her dead fiancé and weeping inconsolably, swearing that she will never love again. Her grieving comes to an abrupt halt with the dramatic entrance of Boris, who is now a guilt-wracked shadow of his former self, tortured by the memories of the murder of the Tsarevich Dmitri. Boris' frenzied state of mind is further inflamed by the arrival of Prince Vasili Shinsky (Nikandr Khanayev), with news of rumors circulating widely that the Tsarevich is alive after all. Shinsky urges Boris to mobilize his military forces because rebellion is stirring among the Russian people and the Poles will inevitably back the False Dmitri. Playing on Boris' distressed frame of mind, Shinsky suggests that Grigori may not have died (recalling that the body failed to decay) and that the Pretender may be, in fact, the real Dmitri. After Shinsky's departure, Godunov sinks into a state of terror, imploring God to have mercy on his sinful soul.

Act III opens in the chamber of Princess Marina Mnishek (Larisa Avdeyeva) in Sandomir Castle (Scene 1), who is the daughter of the Voyevode of Sandomir of Poland. While her maidens-in-waiting sing dainty songs, the beautiful but haughty Marina dreams instead of great heroes and battles from Polish history. She muses on the intrigue of Dmitri (actually Grigori) coming to Poland for help in avenging a great wrong and to regain the throne of Russia. She imagines herself as the Tsarina of Russia, outshining the sun itself. A Jesuit priest, Ragoni, suddenly appears at her chamber door, demanding with religious zealotry that Marina use all her feminine wiles to seduce Dmitri so that she can ascend to the throne of Russia and convert all of the Russian people to the "true faith." Later, in a lovely garden at the Castle of Mnishek (Scene 2), beside a fountain, Dmitri awaits the arrival of Marina, passionately proclaiming his love for her. Ragoni appears and urges Dmitri to hide behind some trees as Marina approaches with an elderly suitor to the accompaniment of a polanaise. Dmitri's jealousy is aroused, but when Marina later returns alone, Dmitri is overcome with love. Marina taunts him, however, demanding that he can only win her love by gaining the throne of Russia. Dmitri wants her to love him for himself, but she dismisses him as a mere vagabond. Resentfully, Dmitri vows to seize the throne but scornfully reject Marina. Marina relents and declares her love for him and the two embrace.

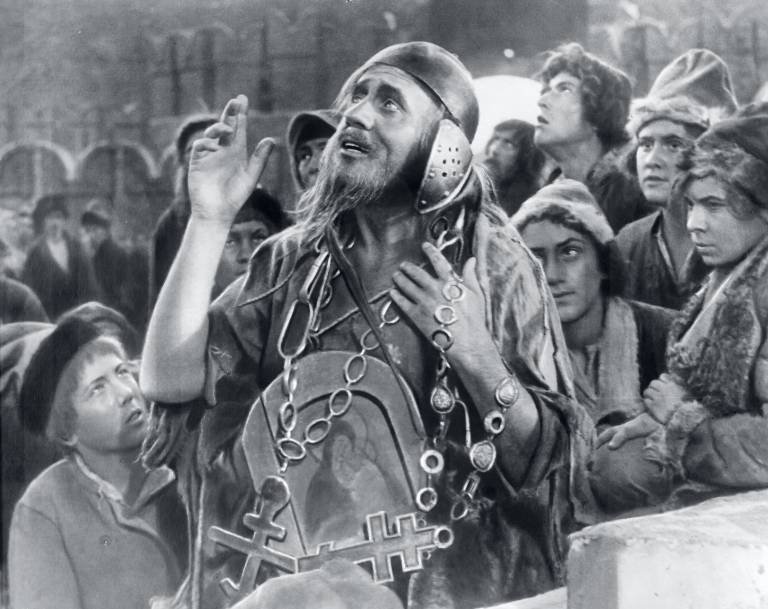

Act IV begins in a square in front of St. Basil's Cathedral in Moscow. There is a crowd milling about as several peasants, including Mityucha (I. Sipayev), emerge from the cathedral, announcing that a curse has been pronounced on the Pretender. The crowd, however, is on the side of Dmitri, imagining that he will arrive in glory, defeat Boris, and help the poor. Offstage, a minor commotion is heard and soon the village Fool (Ivan Kozlovsky) enters, followed by a group of taunting lads. The Fool takes a seat on a rock and sings a gentle song of Jesus. The boys steal a kopek from him and he begins to whine mournfully, just as Boris and the Boyars emerge from the cathedral. Boris spies The Fool and asks him what is wrong. The Fool informs Boris that the boys stole his only kopek and begs Boris to "order them killed, the way you killed the Tsarevich!" All are shocked by this insolence and Prince Shinsky approaches The Fool menacingly, but is stopped by Boris. "Pray for me, blessed one," he says, and then departs. The Fool jumps to his feet and exclaims, "Nobody can pray for Tsar Herod!"

Next (Scene 2), the story is taken up in a forest glade at Kromy. Boyar Khrishov (F. Godovkin) has been captured by a mob of peasants, who are jeering and taunting the bound nobleman. They are joined by Varlaam and Misail, all shouting, "Death to Boris! Death to the Tsar-killer."

In the council room of the Kremlin (Scene 3), the Boyar Duma (the Tsar's councilors) have gathered in emergency session to determine how best to combat the revolt of the peasants and invasion of the Polish army. Shinsky informs the Boyars that he has just observed the Tsar fighting the ghost of a child. As the Boyars reel in consternation, a tormented Boris enters in a trance. Regaining his composure, Boris takes the throne and implores the Boyars to come to his aid in this time of national crisis. Shinsky asks Boris and the Boyars to receive a monk who is waiting outside with important information. Pimen is led in and recounts a miracle that had supposedly occurred at the tomb of the slain Tsarevich, whereby a blind shepherd recovered his sight. Boris shrieks in agony and collapses. Boris calls for his son, Feodor, and the last holy vestments. After offering some parting advice to his son, Boris expires in a spasm of guilt.

The Polish horsemen now charge through the forest glade at Kromy. With them come the Jesuits, singing, shouting, and chanting in Latin, which antagonizes the crowd. The Pretender enters on horseback at the head of a Polish force, urging the peasants to follow him in his march on Moscow. Soon, the stage is empty except for the Fool and a few hungry peasants who sit dolefully while fires of destruction are seen in the background. All he can do is mourn for his beloved Russia as he recites his prophecy.

Themes

The obvious theme is that unbridled lust for power and the pursuit of evil deeds in advancing such ambitions is likely to result in devastating pangs of conscience. My personal view is that evil doers are much more likely to suffer torments of guilt in literature than in real life. Most of the perpetrators of evil acts in real life have long since obliterated any conscience that they might once have had. They may perish by vengeful acts of competitors but seldom from the anguish of guilt. Some of the individual scenes have their own subsidiary themes, such as the power of literacy in the magnificent scene at the Lithuanian border (Act I, Scene II) or the worthlessness of love based on mutual pursuit of power (in Act III, Scene 2). Then, as the curtain descends, the final bleak message becomes evident: The more things change, the more they stay the same. For the tired, hungry, and desperate peasants, one Tsar is as bad as the next. There is seldom any salvation for the poor in political change.

There are a few unfortunate cuts in this 1954 recording. For example, the song of the innkeeper's wife is shortened in Act I, Scene 2. The songs of the children in Act II are shortened or cut. I would have preferred the full score but most viewers won't recognize the omissions and they do little damage to the dramatic thrust of the story. The last two scenes are ordered differently in the Mussorgsky version compared to the later Rimsky-Korsakov versions. The libretto for Boris Godunov is one of the greatest in the operatic literature. My personal advice to viewers of the opera, regardless of version, is to read the plot synopsis before watching the film. That may seem contrary to one's usual views in relation to spoilers, but the story is difficult to follow from a viewing alone and one really wants to concentrate on the beauty of the music more than the story when enjoying opera.

There are many magnificent moments in this opera, but two stand out in particular in my mind as among the greatest scenes in all of opera. The first is Act 1, Scene 2, at the Lithuanian border when Varlaam has to oil up his rusty reading skills or be hanged. Letter by letter, then syllable by syllable, and finally word by word he struggles through the description in the arrest warrant to prove it is not a description of himself. The other scene that is special to me is the confrontation between The Fool and Tsar Boris in Act IV, Scene 1.

There is some magnificent photography here and there in this rendition of Boris Godunov. The film opens with a gorgeous and surreal view of snow falling in Moscow. The use of shadows in Boris' first descent into madness (Act II) is highly effective. The sets and costumes are a highlight of this version, exceptionally faithful to the actual venues and late sixteenth century conditions. The interior scenes in the Kremlin and Polish castles and gardens are enhanced by impressive opulence, in sharp contrast to the cold austerity of the monastery cell.

Mussorgsky's operas are the most "masculine" of the entire operatic repertoire in their subject matter and voice distribution. Before his addition of the "Polish Act," the only significant female characters were the innkeeper's wife and Xenia Godunova. We don't typically apply the terms "chick flicks" or "rooster flicks" to opera, but if we did, the works of Mussorgsky would lie the furthest from the feminine side of the equation. Russia has long been famous for the exceptional quality of their basses and baritones; less so for their tenors and sopranos (with all due apologies to the splendid Galina Vishnevskaya).

One special characteristic of Boris Godunou as a work of art is the extent to which the chorus – standing for the Russian people – acts effectively as another character. The scenes featuring the chorus are skillfully rendered in the 1954 version and the costumes are magnificent. Aleksandr Pirogov, the bass who played Boris, gives an impassioned performance, both physically and musically. His other film work includes a Bolshoi Concert (1951) and Mozart and Salieri (1962). Also noteworthy was the tenor, Georgi Nelepp, who performed the part of Grigori (the False Dmitri). Among the secondary roles, I'd single out for kudos the bass Aleksej Krivchenya as Varlaam. He later appeared in Khovanshchina (1960), also by the Bolshoi and another film in my collection. Otherwise, it would clearly make an appearance in my top dozen that I will be reviewing. Nikandr Khanayev's performance as Prince Shinsky was an exceptional piece of acting though only ordinary vocally. Ivan Kozlovsky was superb as The Fool.

I highly recommend this opera film, especially for those who enjoy historical epics, great tragedies, and raw, rugged, magnificent music. This is not your typical opera. No frilly lace, no impassioned romance, no rotund divas belting out high notes – just hard-hitting, testosterone-saturated epic hatred and violence. Just what you need to get yourself pumped up for a football game!

Electronic-terrorism, voice to skull and neuro monitoring on Hive and Steem. You can ignore this, but your going to wish you didnt soon. This is happening whether you believe it or not. https://ecency.com/fyrstikken/@fairandbalanced/i-am-the-only-motherfucker-on-the-internet-pointing-to-a-direct-source-for-voice-to-skull-electronic-terrorism

Electronic-terrorism, voice to skull and neuro monitoring on Hive and Steem. You can ignore this, but your going to wish you didnt soon. This is happening whether you believe it or not. https://ecency.com/fyrstikken/@fairandbalanced/i-am-the-only-motherfucker-on-the-internet-pointing-to-a-direct-source-for-voice-to-skull-electronic-terrorism

Electronic-terrorism, voice to skull and neuro monitoring on Hive and Steem. You can ignore this, but your going to wish you didnt soon. This is happening whether you believe it or not. https://ecency.com/fyrstikken/@fairandbalanced/i-am-the-only-motherfucker-on-the-internet-pointing-to-a-direct-source-for-voice-to-skull-electronic-terrorism